Lake Titicaca (Spanish: Lago Titicaca) is a lake in the Andes on the border of Peru and Bolivia. By volume of water, it is the largest lake in South America.[2][3] Lake Maracaibo has a larger surface area, but it is considered to be a large brackish bay due to its direct connection with the sea.

It is often called the highest navigable lake in the world, with a surface elevation of 3,812 m (12,507 ft).[4][5]Although this refers to navigation by large boats, it is generally considered to mean commercial craft. For many years the largest vessel afloat on the lake was the 2,200-ton, 79-metre (259 ft) SS Ollanta. Today the largest vessel is probably the similarly sized, but broader, train barge/float Manco Capac, operated by PeruRail (berthed, as of 17 June 2013, at 15°50′11″S 70°00′53″W, across the pier from the Ollanta). At least two dozen bodies of water around the world are at higher elevations, but all are much smaller and shallower.[6]

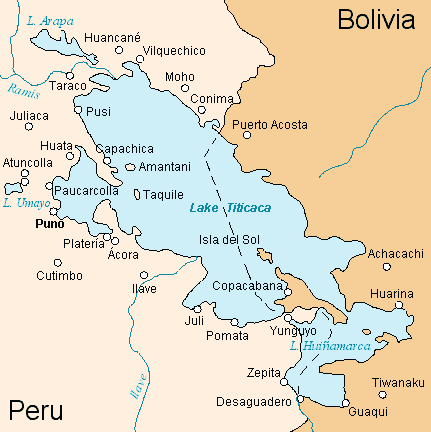

The lake is located at the northern end of the endorheic Altiplano basin high in the Andes on the border of Peru and Bolivia. The western part of the lake lies within the Puno Region of Peru, and the eastern side is located in the Bolivian La Paz Department.

Having only a single season of free circulation, the lake is monomictic,[9][10] and water passes through Lago Huiñaimarca and flows out the single outlet at the Río Desaguadero,[11] which then flows south through Bolivia to Lake Poopó. This only accounts for about 10% of the lake's water balance. Evapotranspiration, caused by strong winds and intense sunlight at high altitude, balances the remaining 90% of the water input. It is nearly a closed lake.[2][7][12]

Since 2000 Lake Titicaca has experienced constantly receding water levels. Between April and November 2009 alone the water level dropped by 81 cm (32 in), reaching the lowest level since 1949. This drop is caused by shortened rainy seasons and the melting of glaciers feeding the tributaries of the lake.[13][14] Water pollution is also an increasing concern because cities in the Titicaca watershed grow, sometimes outpacing solid waste and sewage treatment infrastructure.[15]

The Uros use bundles of dried totora reeds to make reed boats (balsas mats), and to make the islands themselves.[3]The islets are made of totora reeds, which grow in the lake. The dense roots that the plants develop and interweave form a natural layer called Khili (about one to two meters thick) that support the islands. They are anchored with ropes attached to sticks driven into the bottom of the lake. The reeds at the bottoms of the islands rot away fairly quickly, so new reeds are added to the top constantly, about every three months; this is what makes it exciting for tourists when walking on the island.[2] This is especially important in the rainy season when the reeds rot much faster. The islands last about thirty years.[citation needed]

Each step on an island sinks about 2-4" depending on the density of the ground underfoot. As the reeds dry, they break up more and more as they are walked upon. As the reed breaks up and moisture gets to it, it rots, and a new layer has to be added to it. It is a lot of work to maintain the islands. Because the people living there are so infiltrated with tourists now, they have less time to maintain everything, so they have to work even harder in order to keep up with the tourists and with the maintenance of their island.[citation needed] Tourism provides financial opportunities for the natives, while simultaneously challenging their traditional lifestyle.

Much of the Uros' diet and medicine also revolve around the same totora reeds used to construct the islands. When a reed is pulled, the white bottom is often eaten for iodine. This prevents goitres. This white part of the reed is called thechullo (Aymara [tʃʼuʎo]). Like the Andean people of Peru rely on the Coca Leaf for relief from a harsh climate and hunger, the Uros rely on the Totora reeds in the same way. When in pain, the reed is wrapped around the place in pain to absorb it. Also if it is hot outside, they roll the white part of the reed in their hands and split it open, placing the reed on their forehead. In this stage, it is very cool to the touch. The white part of the reed is also used to help ease alcohol-related hangovers. It is a primary source of food. They also make a reed flower tea.

The Uros use bundles of dried totora reeds to make reed boats (balsas mats), and to make the islands themselves.[3]

The larger islands house about ten families, while smaller ones, only about thirty meters wide, house only two or three.[4]

The islets are made of totora reeds, which grow in the lake. The dense roots that the plants develop and interweave form a natural layer called Khili (about one to two meters thick) that support the islands. They are anchored with ropes attached to sticks driven into the bottom of the lake. The reeds at the bottoms of the islands rot away fairly quickly, so new reeds are added to the top constantly, about every three months; this is what makes it exciting for tourists when walking on the island.[2] This is especially important in the rainy season when the reeds rot much faster. The islands last about thirty years.[citation needed]

Each step on an island sinks about 2-4" depending on the density of the ground underfoot. As the reeds dry, they break up more and more as they are walked upon. As the reed breaks up and moisture gets to it, it rots, and a new layer has to be added to it. It is a lot of work to maintain the islands. Because the people living there are so infiltrated with tourists now, they have less time to maintain everything, so they have to work even harder in order to keep up with the tourists and with the maintenance of their island.[citation needed] Tourism provides financial opportunities for the natives, while simultaneously challenging their traditional lifestyle.

Food is cooked with fires placed on piles of stones. To relieve themselves, tiny 'outhouse' islands are near the main islands. The ground root absorbs the waste.

Their stoves for cooking.

The boats, as the floating islands are made of the reed.

Floating Post Office.

Cooking utensils for sale.

No comments:

Post a Comment